Guest Post // "Abram’s Camera" by Nadya Blair

/Abram's Camera

by Nadya Bair

In memory of Abram Strizhevskiy, 1921-2013 and Mira Strizhevskaya, 1924-2016

I can’t remember when my dad gave me my grandfather’s digital camera. It might have been while my grandfather was still at the nursing home, or maybe it was after he died on May 24, 2013. I never used it. I came across it again last summer. That was when I turned it on – just to see if it still works.

That’s when I discovered the last photographs that my grandfather took. They weren’t pleasant.

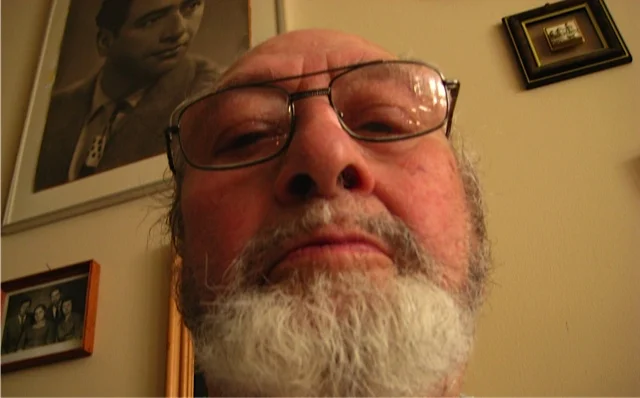

My grandfather, Abram Strizhevskiy, developed Alzheimer’s in 2008. He was disoriented during his last year of living at home with my grandmother, Mira. He sat on the couch of his living room and took most of the photographs from there. Sometimes he turned the camera on my grandmother, and sometimes he’d photograph himself. In the months before he ran away in the middle of the night, covered in his pled, his plaid wool blanket, he thought he was in his Moscow apartment. He would say that the pictures on the wall were arranged just like in Moscow. He’d ask my grandmother whether he was. My grandmother wasn’t sentimental, but she was patient and practical. She’d say, you’re home, you’re in New York. Take a picture of the wall so that you can remember.

I don’t know if he photographed the wall because he was listening to her. He had been a photographer for most of his life, so taking pictures came naturally to him.

In his youth, my grandfather aspired to become a film maker. During World War II he was an aerial photographer with the Soviet Army but after the war, a new wave of anti-Semitism prevented him from finding work in Moscow. He spent nearly a decade as a traveling photographer, working his way through the provinces where he’d take family portraits. When he came back to Moscow, he found a job as an assistant to a camera operator. It was an unenviable job that mostly involved hauling equipment. So he went back to photography, running a portrait studio on Chernyshevsky street in Moscow from the late 1960s until we immigrated in March 1991.

After his death I found this photograph of him with a movie camera.

I hung it up in my living room because I wanted to remember his dream, because I love old cameras, and because I found it uncannily representative of 20th century history. In the foreground is Abram’s Jewfro, sticking up almost as high as the trees behind him. In the background is that quintessentially Russian landscape. Jews and modernity in the foreground, Russia and nature in the background. They’re not exactly at war, but they’re not at peace either.

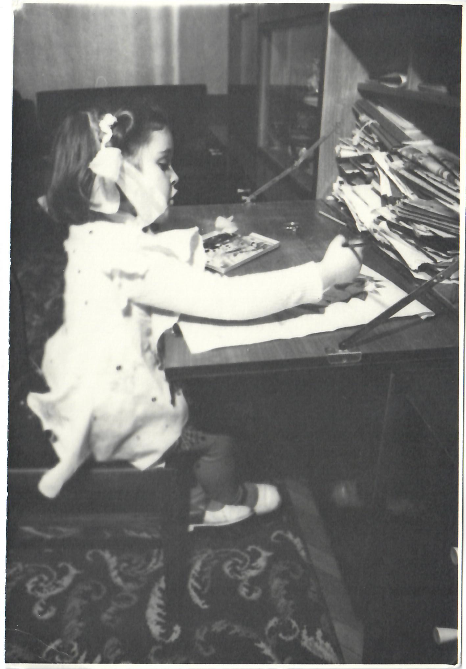

When I was growing up in Moscow, I came to visit my grandparents on the weekends. There was a small forest near their building. My grandfather would take me there to look at the trees and then he’d show me how to draw them. I remember one fall when he brought watercolors and used the side of his brush to cover the page with different color leaves. I tried to master his technique.

On other days we’d set up a darkroom in his kitchen and develop photographs that he had taken of me, my dad, my grandmother. I still remember the smell of the chemicals.

In Queens, my grandparents lived near the Flushing Botanical Gardens. My grandfather never stopped loving the trees, nor the fall colors. He photographed them with his digital camera. Then he came back home to his apartment and watched TV.

I often think nothing confounded and upset my grandfather more than the digital camera he bought. He could deal with the war. He could deal with immigrating to America, and to the boredom and monotony of retired life. But he couldn’t adjust to a camera that kept its pictures hidden inside. He would look at them on the tiny camera screen and say, but how do you get them out?

My grandfather was stuck in his apartment, and in his unreliable mind. He tried to use his digital camera to make sense of what he saw, to jog his memory. But the pictures were stuck in the camera. I don’t think they helped.

“Where am I?”

“Take a picture and you’ll remember.”

“But how do I get them out?”